Here is a problem statement. This article explores its resolution, applying the perspective of a strategic thinker and developing lessons applicable for other situations.

Here is a problem statement. This article explores its resolution, applying the perspective of a strategic thinker and developing lessons applicable for other situations.

Absolut Vodka is a go-to name for ordering cocktails at the bar. But when it comes to entertaining at home, beer, wine, and other spirits are also top of mind. However, celebrations are increasingly happening in personal places – houses, apartments, rooftops, and backyards – especially in the summer. So we wanted to get people thinking of Absolut for all their house party needs.

This was the situation faced by Pernod Rickard USA, the US distributor of Absolut Vodka. Do people buy liquor for home parties because of the quality of the liquor, or for something else? What insights could be useful in constructing a strategy to effectively penetrate home-party market segment. These are the kinds of questions that can’t be determined in data mining and “hard data” analytics.

Absolut Vodka’s Search for Insight & Strategy

To get answers to these fundamental questions, Absolut paid a research company (ReD) to apply its expertise in ethnography. ReD dispatched a team to several locations, including Min Lieskovsky who allows Graeme Wood of the Atlantic magazine to shadow her at a home party in Austin, Texas (see his article titled “Ethnography Inc.” in the March 2013 issue). She spent the evening carefully observing people, especially when it came to activities involving alcoholic beverages. Lieskovsky would watch carefully as guess arrived, greeted the hostess, and interacted with other guests. She would note what happened at each step and note the patterns (which became essential to the strategy).

The academic discipline of ethnography is associated with anthropology, and involves careful observation of native cultures. Now being increasingly applied to business contexts, ethnographers carefully observe people (in this case, the behaviors of party goers) and objects they interact with (liquor). In this case, the researchers were searching for patterns in “the rules and rituals – spoken and unspoken –that govern Americans’ drinking lives, and by extension their vodka buying habits.”

Pattern Searching

In analyzing observations from 18 home parties in Columbus, New York and Austin, Lieskovsky and her colleagues noticed a common pattern in the giving of liquor to the hostess:

“They told anecdotes about their own lives in which the product played a central role – humorous self-depreciating stories about first encountering a vodka, or discovering a liqueur while traveling in Costa Rica or Mexico.”

The anecdotes had to do with humor and adventure. The chemistry of the liquor (Absolut’s branding premise for beverages sold in bars), was of little importance. We’ll see how this pattern was valuable momentarily, but first we need to quickly review the role of sense making in the generation of strategic insights.

Sense Making & the Generation of Strategic Insights

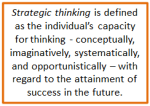

Sense-making is the ability to interpret patterns, where the interpretation forms a story that is relevant to the stakeholder. When we make sense of things, we take the data and look for connections. The result is the ability to gain alignment and commitment in areas that have complexity, ambiguity, or high uncertainty.

Tip: it is often useful to say to yourself, “What is interesting about this?” In this case, gifts were not about alcoholic purity. The gift had deeper meaning revealed something about the story teller’s identity and functioned to make the giver and giftee more intimately connected as people.

Wrapping your product in story is the insight for the product developers. It is an opportunity to develop a marketing brand strategy. Maxime Kouchnir, VP of Vodka Marketing of Absolut’s distributor said, “At the end of the day, we manufacture a spirit, but we have to sell an experience.”

The core insight for marketing Absolut at home parties is to recognize the importance of conviviality and humor. People desire to be conversational and witty.

A Focused Strategy for Home Parties

Good strategies are coherent and focused. Here we have a defined market segment, and we now understand something about the motivations of the consumer. We need to exploit it.

Given the trends for mobile computing, it was natural to develop a mobile application for home party planning. The party planner now has a tool for selecting a clever party theme. Then there are ideas for sparking conversation and wittiness. In Big Spaceship’s explanation, they said, “rather than simply telling people that Absolut is perfect for parties at home, we decided to help them host one. By creating a useful party generating tool we were able to communicate the brand’s message and give people something valuable to use.” In the design of the app, you can draw a direct connection back to the themes found in the research of the ethnographers.

Strategic Thinkers “Go Native”

Now let’s step back. One important learning from this example is that the strategic thinker can gain sights from “going native,” that is going into the field and directly observing the consumer experience.

Obviously, this immersion into the world of the customer takes time. So if you don’t personally think your time is better spent elsewhere, you can still practice strategic thinking by considering questions that need to be asked. Try to step outside the normal frame to discover the crux of the matter.

Another lesson is that it’s not always about hard data. Qualitative data and observation is often the source of powerful strategic insights. Insights come from using empathy and probing for deeper meanings. Often customers see the product entirely differently than does the product developer.

Finally, stay alert for patterns, look for interesting things, and strive to make sense of complexity. Insights will result.

How have you developed a deeper empathy for a business problem?